Navigating seismic restraint compliance in New Zealand’s construction industry can be a tricky task. In a recent webinar, Gye Simkin, our large project lead, shed some light on this topic. He began by explaining the importance of seismic restraints, especially in a country like New Zealand, which has experienced several significant earthquakes in the past decade.

Seismic Restraints and Their Importance

Seismic engineering has seen considerable development in New Zealand, particularly after the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes. These disasters led to widespread damage to non-structural building elements, amounting to around $40 billion in repair costs. Such significant losses have instigated changes to compliance over the past decade, leading to stricter regulations around seismic restraints.

The most commonly designed seismic restraints in commercial interiors include ceilings, non-load-bearing partitions, services such as suspended mechanical hydraulic electrical or fire systems, as well as racking, shelving, and floor-mounted components. They are legally required and considered critical during an earthquake.

Compliance Pathway and Legal Implications

Gye also elaborated on the legal implications around seismic restraints, focusing on the ‘compliance pathway’ – a hierarchical triangle consisting of the Building Act, Building Regulations, and the Building Code. The Building Act, the ‘law of the land,’ refers to the Building Regulations, which in turn describe the details of a building element and its ability to withstand earthquakes.

The Building Code, treated as an appendix within the regulations, defines what needs to comply, and the ‘Acceptable Solutions and Verification Methods’ detail how compliance will be ensured. Interestingly, for seismic restraints, there are no preset acceptable solutions, making the engineer’s job complex.

Challenges of Compliance Pathway

According to Gye, the task of navigating the compliance pathway is fraught with challenges. Standards are often not cited in the building code because the code cannot refer to a draft or yet-to-be-published standard, causing a delay of up to two years in some cases.

For example, NZS 2785, the suspended ceiling standard, is not cited within this compliance, though it is considered best practice. Additionally, partitions, despite being clearly defined as building elements, have no specific standard for design. Further, the fire sprinkler standard NZS 4541 is not cited in the B1 clauses of the building code, where seismic designs fall, but is referred to in the fire clauses of the code.

Key Takeaways

To understand seismic restraint compliance, Gye highlighted two main points:

- The difference between building code compliance and a compliance pathway used by engineers is significant.

- The building design at the time of consent needs to be the final design, regardless of any changes to the standards during the construction process.

In summary, Gye underlined the complexity of seismic restraint compliance in New Zealand and the necessity for engineers and builders to understand the laws and regulations to ensure safety during earthquakes. Despite the challenges, he also pointed out that continual updates to regulations and standards demonstrate a proactive approach towards improving the safety and resilience of New Zealand’s built environment.

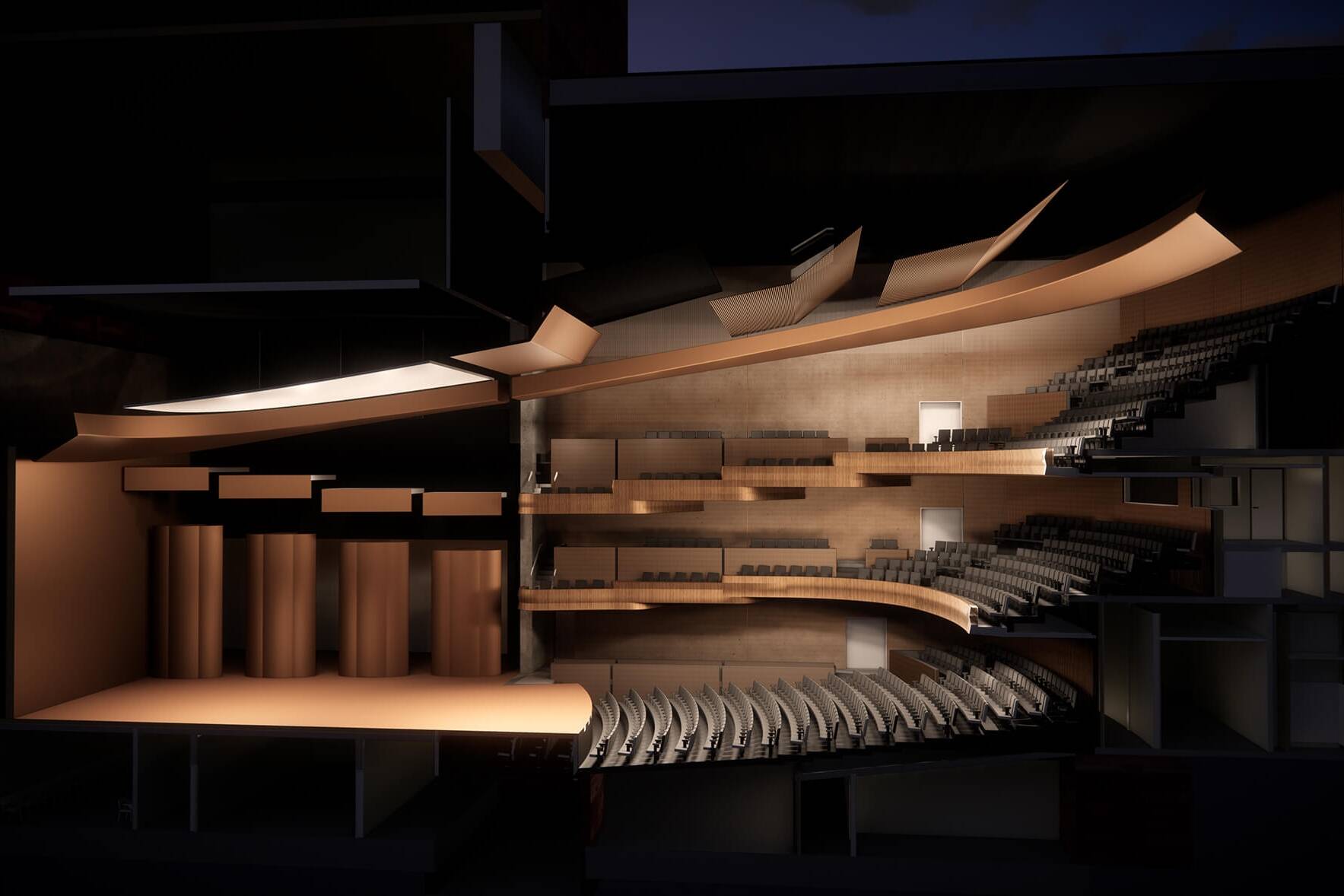

BESPOKE INTERIOR SEISMIC DESIGN FOR WAIKATO REGIONAL THEATRE

One of the stand-out features of the performing arts centre is its main hall, where large sound reflectors are…

Understanding Seismic Assessment of existing Non-Structural Elements in Commercial Interiors

In the latest installment of Team Brevity's technical webinar series, we delved into the critical topic of seismic…

NAVIGATING EXPECTATIONS: THE REALITY OF BIM FOR INTERIORS

The engineering details for interiors tends to be short, fast and with the potential for many clashes, resulting in a…